Meeting place in the garden (after Patrick Geddes) 2005 by Apolonija Šušteršič. Fotos de Apolonija Šušteršič

Meeting place in the garden (after Patrick Geddes) 2005 by Apolonija Šušteršič. Fotos de Apolonija Šušteršič

Meeting place in the garden (after Patrick Geddes) 2005 by Apolonija Šušteršič. Fotos de Apolonija Šušteršič

Meeting place in the garden (after Patrick Geddes) 2005 by Apolonija Šušteršič. Fotos de Apolonija Šušteršič

Meeting place in the garden (after Patrick Geddes) 2005 by Apolonija Šušteršič. Fotos de Apolonija Šušteršič

Garden Service by Apolonija Šušteršič and Meike Schalk. Foto de Apolonija Šušteršič

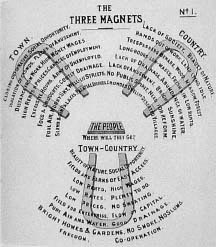

Ebenezer Howard and the three magnets

For cities to thrive, to be communicative and alive, and to function as catalysers of public life it is necessary to stimulate civic participation and community involvement. This at a time when denizens face increased social control, violence, alienation and privatisation of what was previously public. Simultaneously, cities are run as if they were corporate entities driven by profit and urban environments can become more about devising branding advantages to entice investors than about providing adequate conditions for its inhabitants. Manuel Castells, Bernard Tschumi, Paul Virilio, Richard Sennet and Edward Soja, among others, have all commented on the changing meaning of the city and on the fragmentation and dislocation of the urban environment. At times of conurbation, sprawl and megalopolis, even the word ‘city' itself needs attention.

By temporarily intervening in the urban context, by reorganising memories and by temporarily taking on visionary and hybrid roles, for example as roles of designers and urban planners, artists participating in Madrid Abierto think about and relate to the city in innovative ways. As an annual platform, Madrid Abierto facilitate updated and situated accounts of what public art can be today. It challenges ways in which to plan and stimulate social interaction in Madrid. And for those who are curious definitions of public art, one attempt at describing it would be as an interdisciplinary practice involving, among others, artists, architects, designers, planners, writers, dancers and more. Or, as Jane Rendell characterise it "If there is such a practice as public art....then I argue that public art should be engaged in the production of restless objects and spaces, ones that provoke us, that refuse to give up their meanings easily but instead demand that we question the world around us"1. As it stands today, public art comes with massive agendas. Cultural theorist Malcolm Miles describes what he sees as the two main pitfalls of public art: First in its use as wallpaper to cover over social conflict and tensions, and second as a monument to promote the aspirations of corporate sponsors and dominant ideologies2. It is also worth noticing, as Jane Rendell eloquently points out, that traditionally the word ‘public' stands for what is good; for democracy, accessibility, participation and egalitarianism. Set against an increasingly privatised world where ownership, exclusivity and elitist networks rule, it is quite possible the expression ‘public art' need some attention as well.

Given the current framework, where society fails to negotiate the challenges of increased privatisation and where urban developments falls prey for dominating developers, how can art and artists work in order to present alternatives that looks at the situation differently? How can inertia and nostalgia be substituted by visionary and creative tools acting as catalysts for change? Madrid Abierto makes use of provocative and innovative ways to actively contribute to the debate.

With the intention to assist as background information, and to feed a discussion about works that intervene in the city, what follows is a compiled and brief overview of historical initiatives and view points. Using mainly references stemming from city planning, my modest intention is to create a bridge between disciplines, hoping it may benefit art and artists and others involved.

In the beginning were the Viennese architect and planner Camillo Sitte (1843-1903). He is often cited as the founder of modern city planning, something he considered to be art3. In the mid 19th century Sitte toured Europe and tried to identify aspects that made towns welcoming and that succeeded in maintaining a friendly atmosphere. His conclusions, published under the title City Planning According to Artistic Principles (1889), marked the beginnings of a new era of city planning. Here, emphasis was on irregular structures and spacious plazas. "Squares and parks should be catalysers of public life, social condensers able to re-propose the way of life regarded as absent"4. Many of his ideas were similar to those of the British Garden City advocate Ebenezer Howard (1850-1928).

The Scotsman Patrick Geddes (1854-1932), geologist, botanist and later city planner, developed a classification scheme for planning around three components: Place, Work and Folk. In this he concluded that human society could be looked upon in similar ways as animal and plant societies. Geddes perceived of himself as a gardener who ordered the environment for the benefit of life. The difference between creating gardens as places for plant life, and cities as places for human life was, according to Geddes, only a matter of degree: "My ambition being ... to write in reality - here with flower and tree, and elsewhere with house and city - it is all the same"5. For Geddes, the region was to become the visual expression of the order he detected in nature.

Geddes was not concerned with the training of experts. He was far more concerned that the ordinary citizen should have a vision and comprehension of the possibilities of their own cities and actively participate in city planning. His vision included a Civic Exhibition and a permanent centre for Civic Studies in every town. These centres would make efforts to reveal the correlations between thought and action, science and practice, sociology and morals. For this purpose, Geddes bought the Outlook Tower in Edinburgh 1892 and transformed it into a dynamic meeting place6.

Following ideas outlined by Geddes, and now as part of Edinburgh Garden Festival 2007, artist Apolonija Šušteršič worked in collaboration with architect and theoretician Meike Schalk. Their project titled Garden Service was installed as a public art piece along the Royal Mile where Geddes himself lived and installed public gardens. Garden Service consists of benches and a table, flower pots and programmed sessions in the format of Sunday afternoon tea talks. In Geddes' legacy, the discussions were open for all and focussed on architecture, urbanism, city planning, environmental activism and of course on Geddes himself. This is the second project Šušteršič and Schalk produces about Geddes. In 2005 they mounted a glass house along the river in Dundee, the city where he held a position as professor in botany for 30 years. The project was an acknowledgement of Geddes' idea of a meeting place set within a garden. The glass house was equipped with plants, books and other material in order to support meetings and talks held in the house. When the exhibition period was over, the house was donated to an activist group concerned with the future developments of the city.

In the 1960s, especially in the US where pre- and post-war housing shortage and heavy-handed urban renewal strategies resulted in urban crisis, a revival took place in the discussions about city planning. People like Gordon Cullen, Jane Jacobs, Kevin Lynch and many more contributed ideas and developed methods that fed alternative ways to think about the city. Urban design professor Donald Appleyard, for instance, developed a special interest in the psychological effects of traffic that led him to device social network analysis methods which made room for people's own perceptions and values. These techniques allowed Appleyard to bring the inhabitants of cities into the centre of the urban planning process. By devising his own tools, Appleyard took issue with the power conflicts inherent in mainstream urban planning processes7.

1. J. Rendell, Art and Architecture. A place between. London, NY: I.B. Tauris, 2006

2. M. Miles, Art, Space and the City. London: Routledge, 1997

3. P. Rabinow, French Modern. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1989

4. www.sciencenet.com.br/ingles_abril/news/06/03_about.hmt

5. Boyd Whyte, Ian and Welter, Volker M. Biopolis: Patrick Geddes and the City of Life. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2002

6. P. Geddes, Cities in Evolution. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1950

7. www.pps.org/info/placemakingtools/placemakers/dappleyard